Crown Center

In the economic boom decades that followed World War II, real estate developers, city planners, architects, and investors collaborated on the design of a new property type that changed the landscape of cities around the country: the Superblock. Planners conceived the Superblock as a revitalization tool to counter the post-war rise of suburbs that drained commercial and residential opportunities from urban centers. Superblocks were comprehensive, multi-use facilities that also provided a blank canvas to showcase contemporary trends in architecture and landscape design. Unlike the more individualistic, organic growth of earlier commercial business districts, with separate property owners and independently constructed buildings, the Superblock was an intentional, planned development with a single owner who financed and guided the entire project.

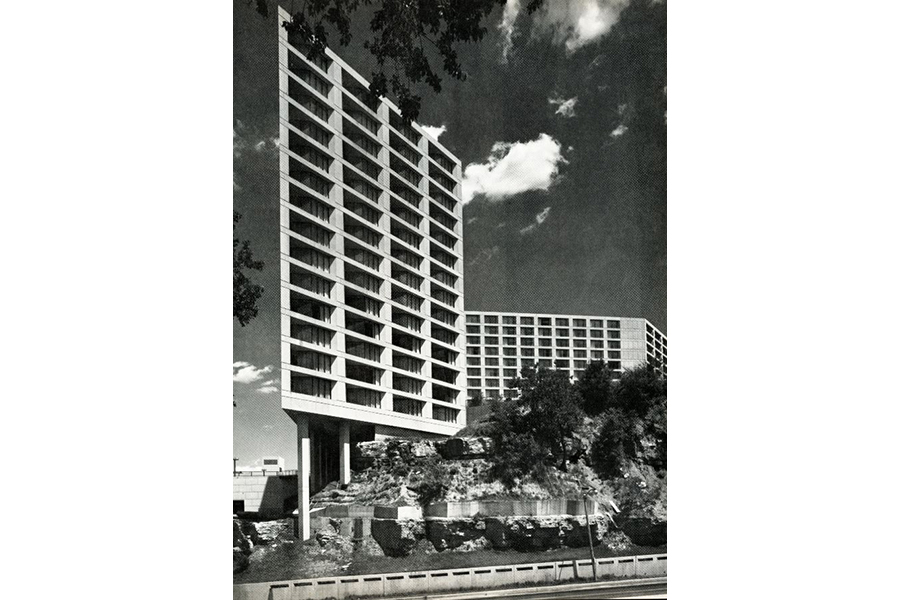

The ownership entity amassed land on multiple adjacent city blocks. Often taking advantage of state or local redevelopment laws, the owner cleared the site for construction of this new mixed-use development, combining the most common urban functions on a single integrated property. The Superblock was a single destination where people could live, work, and play. Multiple buildings and spaces accommodated distinct functions: retail, hotel, office, entertainment, residential, greenspace, and parking. A coordinated design or common aesthetic often unified the development. In addition to using buildings to unify the property, designers manipulated the landscape to guide how people moved through the property, both on foot and in vehicles. This often involved closing or vacating streets to selectively remove vehicles or elevating the primary development area above the surrounding environment to identify the space as separate and apart from the traditional street grid.

Kansas City, Missouri has its own, excellent example of a successful Superblock: Crown Center. In the mid-1950s, Kansas City entrepreneur Joyce Clyde (J.C.) Hall began envisioning a grand future for the underdeveloped industrial and commercial area surrounding the headquarters of his growing company, Hallmark Cards. “Signboard Hill,” across from the original office and manufacturing center for Hallmark, was a blocks-long limestone outcropping plastered with billboards and lined with small buildings. Hall saw this as an opportunity ripe for creating a mixed-use urban community. His goal was for Crown Center to become a catalyst for revitalizing Kansas City in a way that would augment the downtown business district rather than compete with it. In 1966, J.C. Hall’s son Donald Hall chartered the Crown Center Redevelopment Corporation (CCRC) to finance and execute the plan, taking advantage of Missouri’s Chapter 353 Law. This state legislation provided access to tax incentives and to property tax abatement that encouraged inner-city redevelopment by private entities. CCRC hired leading local, national, and international architects and planners, such as Victor Gruen, Edward Larrabee Barnes, Welton Beckett, Kivett & Myers, Hellmuth, Obata, & Kassabaum (HOK), and Harry Weese, to design both the Crown Center Superblock and the individual component buildings, structures, and landscapes. They also incorporated large works of art by Alexander Calder and Gordon MacKenzie into the public spaces, in keeping with Hallmark’s aesthetic for its own facilities.

Construction began in 1968 with the massive excavation required for the first phase: an office building, retail shops, and a luxury hotel. Construction of later phases continued into the twenty-first century. Located just south of the central business district, Crown Center has grown to fill 85-acres of commercial office, retail, residential, and entertainment buildings linked by landscaped public gathering spaces and underground parking. Continuous occupancy of buildings within Crown Center, coupled with synergistic development on the surrounding blocks, illustrates the success of Crown Center as a revitalizing influence. While Crown Center has evolved with the execution of later phases of the redevelopment plan, it retains all the design features and functions that illustrate the significance of this unique property.

Rosin Preservation listed Crown Center on the National Register of Historic Places in 2019. The nomination includes the array of resources – buildings, sites, structures, and objects – that comprise the initial phase of this mixed-use Superblock project developed between 1967 and 1974. The district reflects this new post-war approach to real estate development, as well as design work by the leading planners, architects, and landscape architects of the period.

Address

Kansas City, MO